Module 1 – Lesson 5 – Appendix A

Evidence-Informed Decision Making – Quick reference guide

Evidence-informed practice helps nurses provide high-quality patient care based on the best research and knowledge

Evidence-informed decision making includes a series of steps

- Define

- Search

- Verify credibility

- Appraise/Critique

- Synthesize/Implement

1. DEFINE

Clearly define the research question/problem using the acronym PICO

P – (patient/problem) Describe the problem/patient (e.g. age, gender, hospitalized, in the community)

Intervention

I – (intervention) Intervention of interest (e.g. drug, device, procedure)

Comparator

C (comparator) What you want to compare the interventions against, comparison data sought

Outcome

O (outcome) What outcomes do you want to find out (e.g. Risks/Safety/Death, economic benefit, clinical outcomes, general available evidence)

*Some groups also add in a “T” to reflect timeline for searching of studies or types of studies being sought.

2. SEARCH

Conduct an efficient literature search to ensure comprehensiveness

Planning a strategic and organized search to locate best possible evidence to answer the clinical question.

Within this step, it is important to consider a wide range of databases that might include social and psychological literature sources and qualitative research databases also. A single database (e.g., PubMed) is never enough to ensure a comprehensive search.

1. Use your established PICO search terms.

- Unlike in Google and other search engines, you will not get satisfactory results if you type in an entire sentence as your clinical question. You need to pick out the key phrases, words, and concepts and be specific. Most search engines on credible health research databases or websites respond to common search terms. Use advanced search options within databases to narrow down your search based on your PICO.

- If you type several words without “and” in between, some of the article databases will assume you want only items where those words appear right next to each other, and in that exact order. Use “and” and “or” whenever possible to aid your search.

- PICO can be highly effective to narrow your search and save you time and energy.

- Avoid using Google as your search engine for any health care-related query. (See Dr. Google Handout, CADTH, 2016)

2. Databases are searchable collections of journals. Some examples are:

- CINAHL

- Medline

- CADTH

- PubMed

- Google Scholar* (Beware that Google Scholar indexes a variety of grey literature in addition to peer reviewed journal articles.)

3. Other examples of credible websites and databases are as follows:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services : summaries of evidence, clinical guidelines and more; free

- Best Practice from the BMJ Evidence Centre: clinical assessment tool for practitioners; fee-based

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and technologies in Health (CADTH) is Canada’s health technology assessment agency for systematic reviews of medical interventions, treatment and devices; free

- Clinical Evidence from the BMJ Evidence Centre : summaries of evidence; for medical professionals; fee-based

- Clinical Knowledge Summaries (from NHS Evidence) : evidence summaries; downloadable leaflets for patients, podcasts; for medical professionals; free

- The Cochrane Library from Cochrane : systematic reviews; fee-based or free online access through funded provisions

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK) : synopses of syntheses of evidence; free

- DynaMed from Ebsco : summaries of evidence; for medical professionals; fee-based

- EBM Guidelines from Wiley: practice guidelines and evidence summaries; for medical professionals, fee-based

- Effective Older People Care (beta) from the Cochrane Health Care for Older Peoples Field: a gateway to Cochrane evidence and more for the management of older people’s care and rehabilitation; free with registration

- Evidence Updates (formerly BMJ Updates) from the BMJ Evidence Centre : systematic reviews; PLUS ratings used to help select content; free with registration

- health-evidence.ca: online registry of systematic reviews on the effectiveness of public health and health promotion interventions; free with registration

- Health Systems Evidence from McMaster Health Forum : “a repository of syntheses of research evidence about governance, financial and delivery arrangements within health systems, and about implementation strategies that can support change in health systems”; free

- JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. The Joanna Briggs Institute.

- National Guidelines Clearinghouse from the US Dept of Health & Human Services : clinical practice guidelines; free

- NHS Evidence from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) : meta-search portal for evidence, guidance and government policy data; for medical professionals; free

- nursing+ Best Evidence for Nursing Care from McMaster University’s Health Information Research Unit : systematic reviews; PLUS ratings used to help select content; free with registration

- OBESITY+ Online best evidence service in tackling obesity from McMaster University’s Health Information Research Unit : systematic reviews; PLUS ratings used to help select content; free with registration

- PDQ-Evidence for Informed Health Policymaking provides access to systematic reviews of health systems evidence; put together by a team including members of the Epistemonikos Project, the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services and Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC); free

- PEDro Physiotherapy Evidence Database from the Centre of Evidence-Based Physiotherapy (CEBP) : trials, reviews and guidelines; for medical professionals; free

- Physiotherapy Choices from the Centre of Evidence-Based Physiotherapy (CEBP) : trials, reviews and guidelines; for patients; free

- PIER: The Physicians’ Information and Education Resource from the American College of Physicians: summaries of evidence; PLUS ratings used to help select content; for ACP members only

- PubMed Clinical Queries: evidence-based searching in Medline; free

- Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) from NHS Evidence : a collection of quality and productivity case studies and evidence summaries organized around topic areas; for medical professionals; free

- Rehab+ from McMaster University’s Health Information Research Unit : systematic reviews; PLUS ratings used to help select content; free with registration

- Special Collections from The Cochrane Library from Wiley : thematic collections of evidence on topics such as tobacco addition, breast cancer, and more; free

- Therapeutics Initiative (TI) Evidence-Based Drug Therapy from The University of British Columbia : drug assessments and therapeutics newsletters; for medical professionals; free with registration

- Trip Database: clinical meta-search tool; for medical professionals; free

- UpToDate from Wolters Kluwer Health: summaries of evidence; for medical professionals; fee-based

4. Never limit yourself to just one database or one set of search results.

- Search a database that covers many subjects as well as any subject-specialized databases that may be relevant to your PICO components. The same search phrase entered in two different databases may bring up very different results.

5. When in doubt, ask a librarian for assistance.

- Don’t waste time if you are stuck or encounter something confusing during your searching. A librarian who is familiar and experienced with healthcare research databases can save you time and help you find better information, more efficiently.

3. VERIFY CREDIBILITY

Credible research articles are those published in a peer reviewed journal.

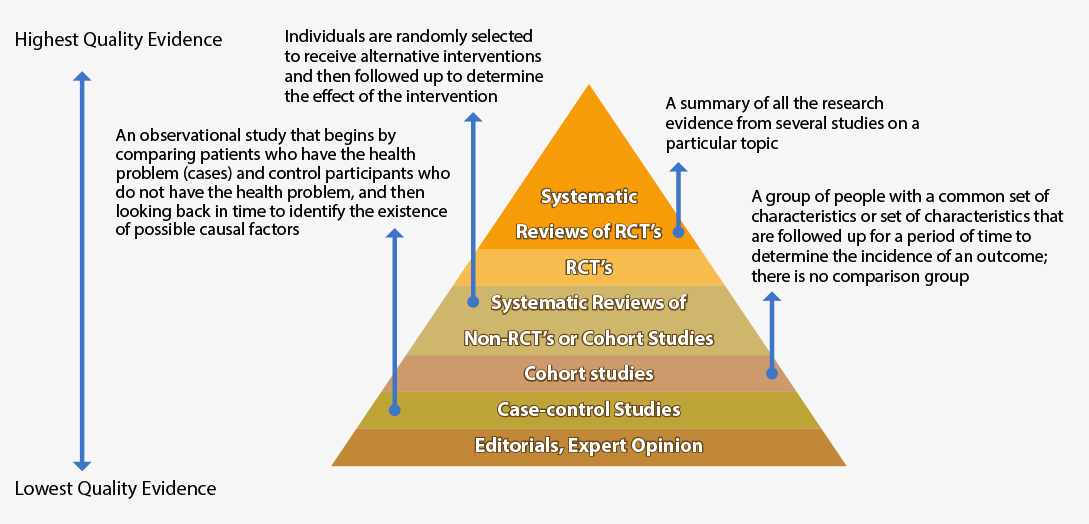

When examining evidence, be aware of the hierarchy levels of evidence depicted below. Not all databases or websites include all forms of high-quality evidence.

When identifying if a website is a credible, you must consider the following:

- Who authored (wrote) the site and what are their affiliations?

- Is the website trying to sell you something?

- Who published and has endorsed the site?

- Look at the domain name of the website.

- .edu = educational

- .com = commercial

- .mil = military

- .gov = government

- .org = non-profit

- What is the main purpose of the site? Why did the author write it and the publisher post it?

- What is the quality of information provided on the website—is there evidence of peer or external reviews?

- Does the author cite sources and provide references for any summarized info provided?

- How frequently is this website updated?

- How does it all add up?

4. APPRAISE/CRITIQUE

Critically examine the literature. Was the study done well enough that you can be confident in its findings?

- Critical appraisal tools help to identify research flaws in studies and help health professionals to decide and assign a level of “quality” to the evidence before using the research findings.

- They help you to think critically about what you are reading and decide on its true value.

Below are some tools that can be used for critical appraisal of research and clinical practice guidelines:

Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Tools

Randomized Control Trial (RCT’s) Critical Appraisal Tools

Qualitative Studies Critical Appraisal Tools

Critical Appraisal Tools for Multiple Research Types including Systematic Review

Considerations for Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) are more practical research-derived documents created from multiple sources of evidence and by clinical practice experience experts. Quality CPGs use the highest quality evidence available to help inform practical clinical actions to improve patient outcomes.

CPGs have been officially defined by the Institute of Medicine as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options” (National Institutes of Health, 2011).

When rigorously developed, guidelines can effectively translate the complexity of scientific research findings and other evidence into practical and actionable recommendations.

However, not every CPG, is created using rigorous and carefully defined systematic approaches. Some CPGs have not included a sufficiently comprehensive literature search to retrieve all forms of research on a clinical issue, and some have not been appropriately vetted by experts and patient groups. Not all CPGs clearly rate the quality and value of the specific evidence they are using.

Using CPGs in practice

Grimshaw, Eccles and Tetroe (2004) and Dahm et al. (2009) identified several other challenges with locating and using CPGs in clinical practice, including:

- Conflict of interest among the guideline developers that are not declared appropriately

- Poor management of conflict of interest in guideline writing by experts

- Lack of transparency regarding the methods used to develop the guideline

- Insufficient consideration of relevant patient characteristics when developing the guideline

- Low quality or no evidence underlying the recommendations or guidelines cited or defined

- No consideration of the economic, patient or caregiver impact

- Guidelines for multi-morbidity conditions that are in conflict with each other

- Conflicting or confusing recommendations or guidelines across various groups for the same disease condition

- Guidelines that are not reviewed or updated when new evidence becomes available

Guideline development

Recently, international groups such as Guidelines International Network (G-I-N) , have begun collaborating with recognized guideline development groups to provide improved quality development for CPG processes. G-I-N has developed high-level standards for guideline development. While quality of guidelines internally is improving, much more work is still needed.

Critical appraisal of clinical practice guidelines:

CPGs require a separate critical appraisal tool to best check for quality.

Some of the absolutely essential components included in any critical appraisal tool which should be applied to any clinical practice guideline are:

- author’s affiliations and groups that have endorsed the guidelines;

- conflicts of interest for those developing the guideline;

- type of literature search to ensure inclusiveness of research in guideline development;

- rating quality and methodology used to determine the quality of the rating scale used for a particular guideline;

- verification that guidelines presented are clinically practical and actionable; and,

- commitment for guideline update at a designated future time.

Clinical Practice Guideline Critical Appraisal Tools

Related Resources:

- An excellent resource to consult with searching for credible clinical practice guidelines is the National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC).

References:

- Grimshaw, J., Eccles, M., & Tetroe, J. (2004). Implementing clinical guidelines: Current evidence and future implications. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 24(Suppl 1), S31-S37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340240506

- Dahm, Pl, Yeung, L L., Gallucci, M., Simone, G., & Schuremann, H. J. (2009). How to use a clinical practice guidelines. The Journal of Urology, 181, 472-479. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.041

4. SYNTHESIZE & IMPLEMENT

Synthesize the results of the most credible and most relevant research articles to arrive at a single appropriate conclusion to answer the clinical question. Assess the ‘fit’ with the research question, and incorporate the findings into clinical practice. Remember to consider your patient’s values and your own experience in this process.

References:

- Lobiondo-Wood, G., Haber, J. (2013). Nursing research in Canada: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidenced-Based Practice (3nd ed). Elsevier Canada; Toronto, ON.

- University of Texas at Austin, Education Library. How can I tell if a website is reliable?

- Canadian Agency for Technology and Drugs in Health (CADTH). (2016). Learning Centre.

Related Resources:

- Canadian Agency For Drugs And Technologies In Health (2016). “13 considerations for evidence-informed decisions”

- Beyea, S.C., & Slattery, MJ. (2006). Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing. A guide to successful implementation.

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. (2012). Introduction to Evidence-Informed Decision Making Online Module.

- Can-Implement Guideline Adaptation Tool.